I've been thinking about what makes a movie powerful.

A view of the (asbestos!) curtain at the 1930 vintage Pantages Theatre. Source: California State Library.

I grew up roaming Hollywood Boulevard when there were more than a dozen movie theaters along the one mile stretch between La Brea Avenue and Bronson Avenue. In our early teens my friends and I knew how to sneak into most of them without paying the quarter it would cost to buy a ticket. Not surprisingly, I fell in love with the movies and now my memory carries a collection of classics I can visit in my imagination: The Wizard of Oz in a 1950s rerun at the Hawaii Theater; Around the World in Eighty Days in 1956, the same year Charlton Heston smashed the two tablets etched by God’s finger with The Ten Commandments.

When 1955s Rebel Without a Cause played in at the Pantages Theater, one friend bought a ticket then skipped down the eastern aisle opening all the exit doors so dozens of us could sneak in to see our friend from school’s brother who was one of James Dean’s tormentors in the film. Becky and I paid little attention to one another, a rarity, while watching Psycho at a Burbank drive-in theater in 1960, terrified teenagers one year into dating one another. The following year, we snuggled next to one another in Grauman’s Chinese Theater to watch Natalie Wood in West Side Story.

Decades later, we and three other couples along with our eleven children watched the original Star Wars (with that goofy bar band of intergalactic musicians) at the Academy Theater in Pasadena. Perhaps because I’m a psychotherapist, I still consider 1975s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest my all-time favorite, as Randle McMurphy torments and is tormented by Nurse Ratched while surrounded by his new psych ward pals. I had to leave my seat in the den when Jodie Foster staggered in the dark while being stalked from behind by Buffalo Bill with his infrared headlamp in 1991s The Silence of the Lambs, the most frightened I’ve ever been watching a film. Cuckoo’s Nest, Silence of the Lambs, and 1934s It Happened One Night are the only films to win the top five academy awards: picture, actress, actor, director, and screenplay.

If you’re at all a film fan, you’ve either seen or heard about many of these classic films and, I’m certain, have your own more-up-to date memory-theater where your favorites play on demand. Most of my memorable films were big, loud, culturally important – perhaps legendary. Recently, however, I fell in love with two films that are small, quiet, culturally ignored, and anything but legendary. But they’re very good, and if you’re a movie fan they’re certainly worth putting in your Netflix queue.

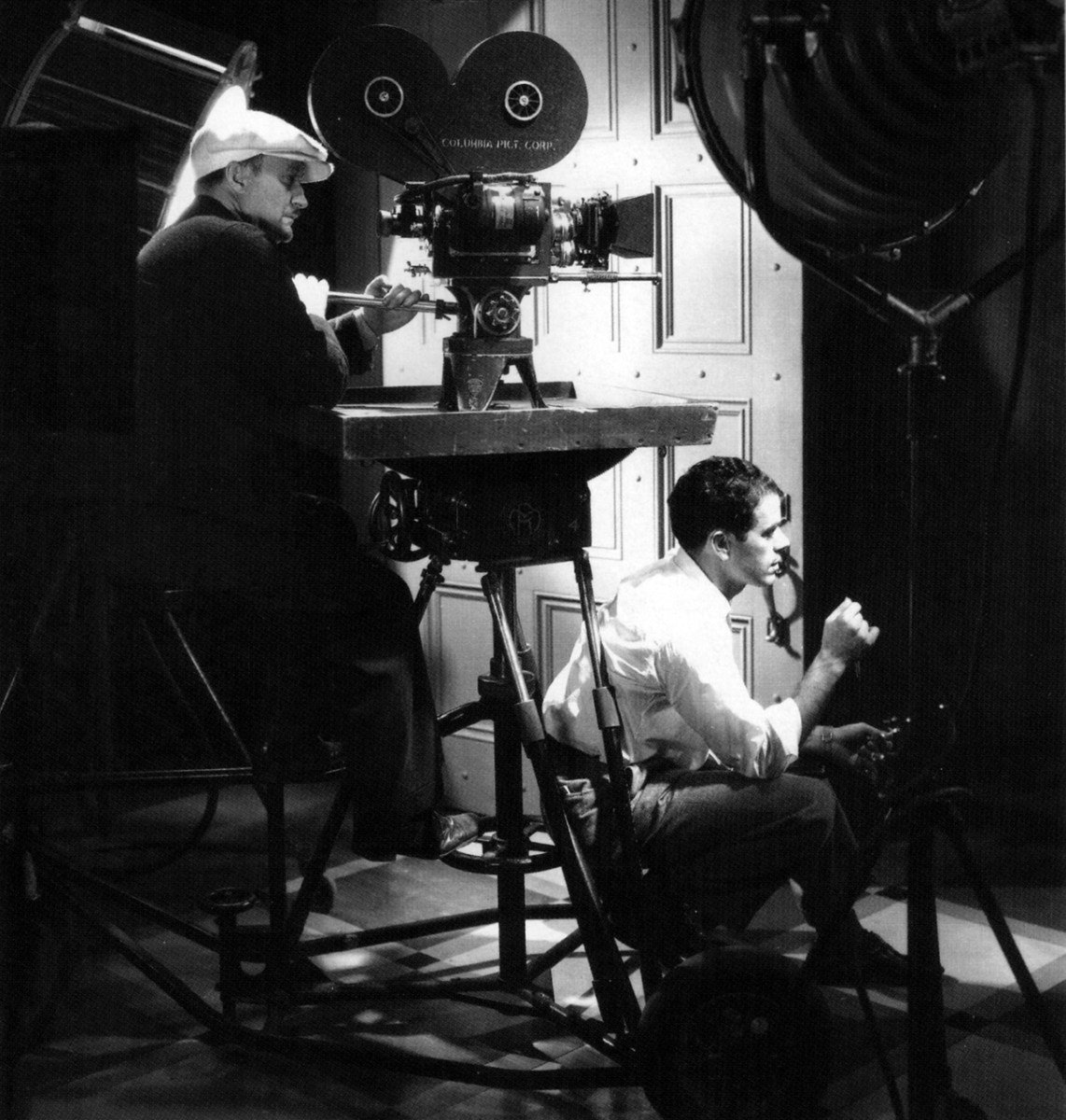

Joseph B. Walker, ASC and director Frank Capra are set to roll while shooting the Pre-Code Columbia Pictures comedy It Happened One Night (1934).

In Leave No Trace (2018), Will is a vet from an unnamed war with a serious case of PTSD which renders him frightened and helpless living among the general population. So he takes his daughter, thirteen-year-old Tom, into the dense woods of a National Park in Oregon where they live in hiding as survivalists, eating what grows wild around them, avoiding human contact. The remainder of the plot involves them being caught by Rangers, forced to rehabilitate in government-sponsored housing, then jumping a train to Washington where they again set up a survivalist home in the dense forest.

What propels this simple story is the quietness of their surroundings, the intimacy of their relationship, the candor and affection of their conversations, and Tom’s emerging realization that their life in the forest works for her father but no longer works for her. What’s wrong with you isn’t wrong with me, she tells him at last, and the final, quiet drama of the film is their resolution of this conflict.

Without violence or sex, with no Computer Generated Images of explosions or stunts, this is a film about two people who are deeply attached but find themselves pulled in different directions by the efforts each of them makes to be faithful to themselves. Ben Foster as Will and Thomasin McKenzie as Tom are terrific, as are those few in the spare supporting roles.

Actors Ben Foster (Will) and Thomasin McKenzie (Tom) with Leave No Trace director Debra Granik.

Becky and I first saw Leave No Trace when it screened in 2018. When we saw Causeway (2022) this winter, I said immediately afterward that it reminded me of Leave No Trace: another small film, driven by conversations between two very different people, each of them lost and searching for some way out of the fog.

Lynsey is home from the war in Afghanistan where an Improvised Explosive Device blew up her military vehicle and damaged her brain. It’s painful to watch as she struggles through rehab, determined to recover so she can redeploy back to the war, which is our first clue that she’ll do even this most foolish thing to keep from moving back in with her listless alcoholic mother. She recovers enough to get a job cleaning pools and, when her old pick-up truck needs repair, meets up with James, the mechanic who agrees to fix it.

Causeway promotional poster featuring Jennifer Lawrence.

From their first conversation, it’s clear that this is a new kind of engagement for each of them: the candor, the silliness, the comfort with one another. As with Will and Tom in Leave No Trace, Lynsey and James stitch themselves to one another in an intimacy that glances off their only moment of physical affection and keeps probing: What do you want from me? What do I need from you?

Jennifer Lawrence is one of the most beautiful women in movies, and the genius of her character in this film is that she’s scrubbed clean of any make-up or fashion and all we seen is the plain, fresh beauty of her face. (She managed this same plain look in her 2010 movie, Winter’s Bone, for which she won an Academy Award nomination when she was twenty years old. But that film, also small and intimate, was so harsh and dark that, unlike these two films, it’s hard to recommend without warning.)

Brian Tyree Henry, who is James in the film, was just nominated for a Best Supporting Actor award, which is remarkable considering how small this film is and how few people have seen it. James’s vulnerability and history of pain live in his eyes and lend credible reason to the generous quantities of beer and weed he uses to medicate himself.

Each of these films has a quiet, perfect ending.

I'm sure a big, powerful movie will win Best Picture this year, and no doubt I'll find a way to see it. But if I choose to rewatch a movie, it will more likely be a Causeway than Top Gun: Maverick. Perhaps it’s this stage in my life, but the power of personal intimacy is much more compelling that whatever power there is in spectacle and violence and loud noise.