I've been thinking about old friends.

We finally broke out of our Covid isolation on a Sunday evening in February and hosted a dinner party for seven very close friends, all of whom we’ve known for years. A few hours before they arrived, as we were preparing for dinner Becky dug out from a low kitchen cabinet a large parquet salad bowl.

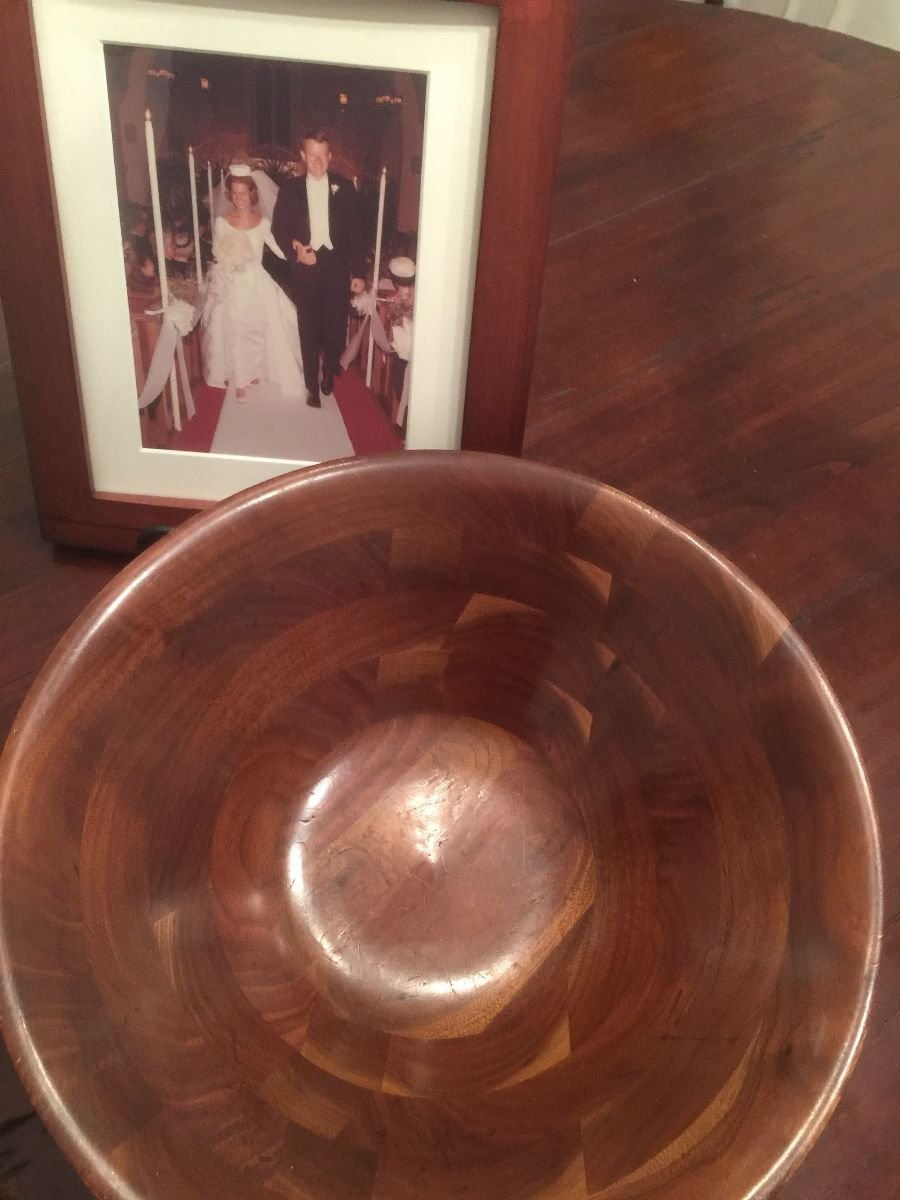

As soon as I saw it I laughed out loud and said, Ah! Dear George, referring to one of the friends who would soon join us for dinner. It turns out this was his wedding gift to us fifty-nine years ago, which Becky reminded him of when he arrived.

At eighty and seventy-eight, Becky and I have friends we were in classes with from kindergarten through high school, and several friends we met in college and graduate school. With many of these we’ve shared the births of children and grandchildren, their baptisms, bar mitzvahs and bat mitzvahs. When these children became adults, their lovers and partners brought into our extended family their own habits and convictions that widened our vision.

We’ve included Republicans, Democrats, Independents, radical from the right and the left, and none-of-the-aboves; working class families and the filthy rich; world travelers and a few who refuse to drive the freeways in southern California; people of deep faith and several with little or none. With all of these dear ones, we’ve been through long term marriages, separations and divorces; we’ve attended memorial services for parents, partners and children, and are now showing up at one another’s retirement parties.

Gordy, Sandy, Becky and me at UCLA in 1962. Gordy emailed this to me before I started writing this piece, just to remind the four of us about how long we’ve known and loved one another.

I grew up in a family where hospitality was a necessity before it turned into a habit. I never knew my father’s Massachusetts family; his parents died before I was born, and his siblings never left the northeast. My mother and her five siblings had twenty-one children, most of whom lived, and still live, in or around Los Angeles, so there was always a meal, a bed or a couch, sometimes a sleeping bag on the floor.

In the early 1950’s, my uncle and pregnant aunt and their two-year-old son moved into an old, rambling stucco house in Hollywood with the seven of us, plus my grandfather and an aging family friend. I stayed with another aunt and uncle and three cousins each time my mother gave birth to one of my four younger siblings. One of those cousins later shared a twin bed with me for a season when I was a high school basketball player and he was the same school’s starting linebacker. I moved back in with his family for the first semester of my senior year in college. He was Best Man in our wedding.

By the time we were old enough to invite friends over, my father had coined a phrase that defined our entire clan’s culture: Sure, invite them. We’ll just add water to the soup.

So for overnights and weekends, there were always available spaces. The last June day of my junior year in high school, I asked if a baseball teammate could spend the night. Of course he can. He stayed until Labor Day. Neither of my parents asked why, but midway through the summer my dad bought him a second pair of jeans and three white tee shirts. We’ll just add water to the soup.

The Clan Gathers: Fourth of July in my aunt and uncles’ back yard in Burbank, around 1959. My father was still in his red pajamas as we prepared to set off fireworks! Surely there’s a story there.

It was my generation – these siblings and cousins and our cohorts – who extended the boundaries of this invitation. One sister married a Latino, which caused my father to finally learn the proper ethnic and racial designations for his new son-in-law and the non-white, non-Christian, non-straight successors who soon joined the family. This widening clan included a hippie astrologer, a beautiful Black baby cousin, and a slew of racial and ethnic Beloveds.

A cousin who remains among my closest friends was the first one to bring home a same-sex partner; decades later she married a woman (I officiated at the ceremony in our living room) with whom she has what most of us agree is the sanest, most solid marriage in the clan. This transformative experience of inclusion may seem dated to our children and grandchildren, but for us and our parents it was a revolution.

It was this family’s open-heartedness that gave birth to what is now the treasure of old friends. Once people moved into our hearts, they took up residence like family, and stayed for soup.

Three generations of girl cousins at Christmas tea (December 2015)

In my first year in graduate school, Becky and I moved into a small cottage outside Princeton in what was a summer vacation village for New York Scandinavians. In our first week there, we ran into Mel and Marti, another seminary couple who had found this quaint community.

Soon Mel and I were commuting together to classes and Becky and Marti were figuring how to communicate with husbands who talked about eschatology and hermeneutics as if these were the most important subjects in our lives. These two working women rescued us for weekends of home-cooked meals and cheap wine. In the decades to come, we had children at the same time, and Mel and I - both having served in the church - left to become therapists. Marti died nearly twenty years ago; I still have lunch with Mel about once a month. Literally and metaphorically, a lifetime together.

Covid was a test of friendships for me. Our physician daughter monitored us as if we were her children, providing us with masks and sanitizers in the first days of the pandemic, scheduling our vaccinations and boosters as soon as they were available, and insisting on strict rules for social interaction. All of this made most of our friends inaccessible except by phone or that monster spawned by the virus, Zoom.

But without letting on, we’d sneak for drinks or dinners to the patios of the few friends we found indispensable. It’s not that we let go of other friends; it’s just that these few were friends even a plague could not keep us from.

Lunch with Greg, one of the friends I’ve had one-on-one Friday lunches with at the same restaurant table for thirty years

I wonder now how the pandemic will influence other old friendships. I wonder whether this two-year hiatus has been just a temporary separation, or if the separation has created a drifting apart that we’ll never repair. I know that a few of our friends refused and still refuse to be vaccinated or masked, which takes them off our list of people we want to hang out with.

To be fully candid, with some old friends these differences in dealing with the virus come on the heels of four years of political fracturing that seems irreparable.

We’re part of that national tragedy of red and blue that is not inclined to seek purple, whether in politics or continuing intimacies; we’re pretty much done with one another, certainly in terms of the affections we’ve shared in the past. It's hard to trust, much less to love, people whose ideas and behaviors are so alien to me.

Perhaps it’s a sign of small-mindedness and a betrayal of my father’s dictum about adding water to the soup, but my indispensable friends are very much like me. They include a diversity of race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation, and range in age from children to people even older than I.

But are we really that diverse? Most share my political and religious convictions, and most are, as I am, intellectually curious and relatively affluent. Maybe I’m just too old for conflict or irritating differences, the kinds of combat I used to thrive on.

I still care in some vague, distant way about those friends who differ from me, but neither they nor I set a place for one another at the table.

I’m grateful that Becky and our children, their partners and our grandchildren are a permanent and safe home. I feel fortunate to have been raised in an extended family that still surrounds me, and George’s salad bowl and his continuing place at our table remind me that old friends – those whose stories I know as they know mine, and whose values and commitments I share – are shelter from any storm.

A week after our February dinner party, I got an email from George suggesting we set a date for our next Friday lunch, just the two of us. I can’t wait.

Blessings,

Rick

Hi, I’m Rick Thyne and I’m grateful that you found your way to these pages. Perhaps in these conversations we’ll find our way to more of the common good that is - for me - our best hope for a future in which all of us thrive. If you've found this column and would like to get my latest column delivered, free, to your inbox every two weeks, you can subscribe now.