I've been thinking about how I learned that I’m not normal.

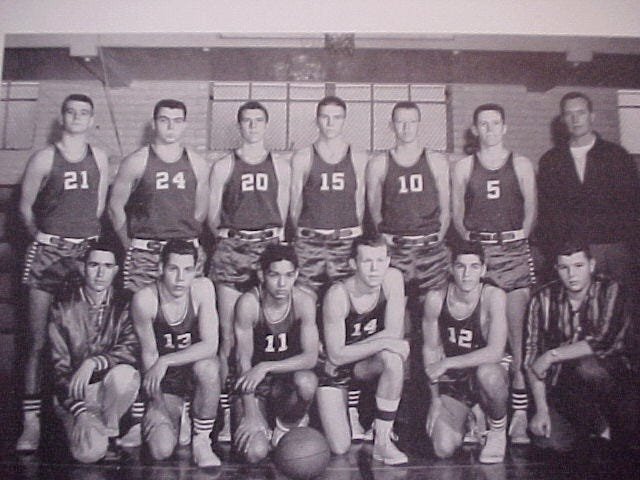

The only thing I knew about Black people while I was growing up was that I was afraid of them. Well before the Civil Rights Movement, I was raised as a white boy in a family and culture that were blatantly, comfortably racist in language, social prejudice, and politics. I played high school basketball in Los Angeles in the 1950s and had my first contact with young Black men in the safety of school gymnasiums, but I never followed up on any of those contacts. I went back to my white world knowing now that there were people out there not like me, whom I didn’t understand and who (I presumed) didn’t understand me. I was still afraid. I never made a Black friend.

I learned more about what it means to be white and frightened while riding fusty, creaking elevators and walking the dimly lit, menacing hallways of dilapidated 1960s housing projects in Newark, New Jersey, afraid that I might be assaulted. I was there to visit parents of young Black kids, encouraging them to enroll their children in a nearby church tutoring program that I directed. I assumed they would be awkward with me since I felt so awkward sitting with them in what to me seemed such small, cramped apartments. Instead, I encountered mostly surprise that a six-foot four-inch thin young white man with a crew-cut was at their tenement door; still, they let me in. For the first time, I began to wonder if it was not the danger which I imagined Black people posed that created the distance between us, but my own discomfort. I was still afraid.

The dedication of the Rev. William P. Hayes Homes, named for a well-known Newark clergyman, took place on June 25, 1954. Via Newark Public Library.

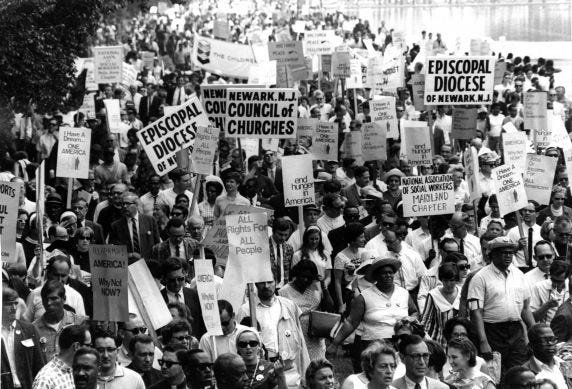

A few years later, I walked with Trenton’s Black community in a curb-to-curb crowd during The Poor People’s March. I was a pastor in nearby Lawrenceville, New Jersey, and studying for an additional degree at Princeton Theological Seminary just a few miles away. As busy as I was in my job, I knew I had to get to the March, certain that all my liberal Seminary professors and my progressive friends from our parish would be there. I didn’t want to be among those who failed to show up, especially in the still-emotionally tense weeks following Dr. King’s murder.

I parked a few blocks from the parade route and, walking around a corner, was suddenly engulfed in a sea of Black people marching at a funereal pace behind the mule-driven cart that two months earlier had carried Dr. King’s body after his memorial service. I looked for my professors and church friends but through the mile-long march mine was the only white face I saw in the crowd. Arm in arm, I sang with the older Black man on my left and the young Black woman on my right, Ain’t gonna let no white folks turn us around.

The Siren Vase, 480-70 BC, via the British Museum, London. Ulysses is bound to the mast, to help him resist the call of the winged Sirens overhead.

As in those Newark apartments, it dawned on me once again that I was a part of the problem. As part of the family and culture I was raised in, I was one of those white folks who, for generations, had turned Black people around, kept them on the margins. Maybe the major problem between us was not that they were Black and strange and dangerous, but that I was a white man in a predominantly white world whose oppression of Black people I was only beginning to understand. If I could get past my fear of them, perhaps I could come to realize that this lack of understanding on my part was near to the heart of the problem between us.

Hollywood High School is on the corner of Highland Avenue and Sunset Boulevard, a block south of Hollywood Boulevard. In the late 1950s, Coffee Dan’s, near the corner of Hollywood and Highland, was a refuge for gay men at a time when it was dangerous for them to be in public who they were in private. I often walked home after school and on occasion, to impress my friends, I would yank open Coffee Dan’s tall glass front door and shout Queers! or Faggots! then race a mile down the boulevard toward the church gym to squeeze in one more three-on-three basketball game before Wednesday evening prayer meeting began.

Through college and graduate school, I made my intellectual and spiritual ways toward acknowledging the shame of my teenage behavior and realizing that LGBTQ+ people are not God’s mistakes, as I had defined them then, nor a threat to straight people, nor to children. But it wasn’t until the mid-1970s that I loved a gay man; that happened when I hired Roger as minister of music in the church I then pastored, and he came out to me. He invited my wife and me into his queer world where men and women welcomed us as their friends and took us into their gay and lesbian parties and activist politics. As we grew closer to several same-sex couples, we learned first-hand that their intimate relationships felt very much like the intimate straight love and commitment Becky and I shared.

The privileges and respect that came naturally to us were hard-fought battles for our new friends. While we were treated as normal, they were subjected to derision and moral judgment, many of them banned not only from public acceptance but from their families and their worship communities. Later, during the AIDS plague, they were told that this killer was God punishing their community for being who they were. When Roger died five years ago, in his mid-seventies, he was out to his friends and siblings, but he continued to live in hiding from much of his conservative Christian extended family and from members of the congregations for whom he provided sacred music. Such disdain and rejection were never heaped upon me for being straight.

Police officers remove members of ACT UP, who staged a sit-in to protest the AIDS crisis inside the hallway of the New York State Capitol in Albany on March 28, 1990. Bettmann / Getty Images

In my teens and twenties, I started to realize that all persons are created equal was not just my national heritage but an accurate reflection of the teaching and witness of the first-century, brown-skinned Jewish rabbi to whom I committed my life long ago. It took longer to learn that I am not normal or, more precisely, I am not the norm. As a straight white male, I do not embody characteristics to which all non-straight, non-white, non-male people should aspire.

Roger and his gay friends and the vast crowd of LGBTQ+ people in my current congregation and community shouldn't have to need to mimic straight people like me in order to fit in. They deserve the same rights and privileges as I do, without the unfair obligation to relate or believe or act like I do. They ought to be able to dress and believe and speak and love one another in any way that is comfortable for them, whether they look like me or not. The same is true in our wider culture. Wouldn't it be nice if a Jewish Kippah seemed to all of us as American as a cowboy’s Stetson, a Muslim woman’s hijab as American as a red MAGA baseball cap? Different, but not normal and abnormal.

Those Black kids in our tutoring program, their parents, and the crowd following Dr. King’s burial cart should not have to need to be like me or aspire to what I aspire to in order to be as worthy of the respect and dignity that I believed I was entitled to. Just as I have my stories of Irish ancestors and parents without high-school diplomas, of too much alcohol and unbridled impulsivity, they have their own defining stories. Different heroes, different villains, different tragedies, different triumphs - but not a story I need to be afraid of.

It took me too long to realize that the people I was afraid of were the very people I was oppressing. They lived on the margins with their own joy and anger because people like me put them there and kept them there. They were abnormal, that is, not like me, because people like me kept them from rights and privileges we took for granted, the world we thought of as normal.