I've been thinking about needing to be right.

Lee Daniel’s The Butler (2013) is a film loosely based on the true story about an African American man, Eugene Allen, who worked as a White House butler for every president from Eisenhower to Obama. He was silently present in the Oval Office to overhear conversations about major issues that arose in each of the twelve administrations of his tenure. The film centers on the most pressing justice conflict each president had to deal with, including sending troops to help integrate Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957; the Civil Rights movement of the late 1950s and 1960s; a half-century of wars in Vietnam, Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan; the rise of women’s liberation and gay rights, and the collapse of the economy in 2008.

BECOME A FREE SUBSCRIBER TO I’VE BEEN THINKING

As my wife and I walked out of the theater she asked, What did you think of it? I remember my response vividly because it is so blunt with ignorant self-congratulations:

On every one of those issues, we were on the right side.

I’ve lived through and participated in many of the progressive movements of the past seventy years and, with evidence to support me, settled into the conviction that the arc of our history does in fact bend toward justice. I convinced myself that the story of the twentieth century had, essentially, a happy ending: that we had made significant and permanent changes in our culture.

It turns out that this assumption was delusional. It is lazy thinking to believe that progress is inevitable and even more foolish to believe that we’ve not only overcome significant forces of social oppression but have become a liberated society.

Donald Trump’s re-election shattered this illusion. As of January 20th, a different majority has now taken over all three branches of our federal government, representing a powerful backlash to seventy years of progress. As he selects his cabinet and administrative staff, it's clear that the government will be run by right-wing ideologues and plutocrats. On his first day in office, Trump used his executive order powers to challenge birthright citizenship guaranteed in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution (and crucial particularly for people of color); dismissed any sense of the rule of law by pardoning 1,600 convicted January 6th criminals; and opted out of the Paris Climate Agreement, the most significant international effort to halt the rage of climate change.

These leaders don’t believe in democracy, at least not in the two convictions at the heart of our heritage: that all of us are created equal, and that every qualified citizen has a right to vote. They believe some of us (meaning they!) are better and more important than the rest of us, and voting must be gerrymandered and suppressed so that the majority cannot win against this autocratic minority.

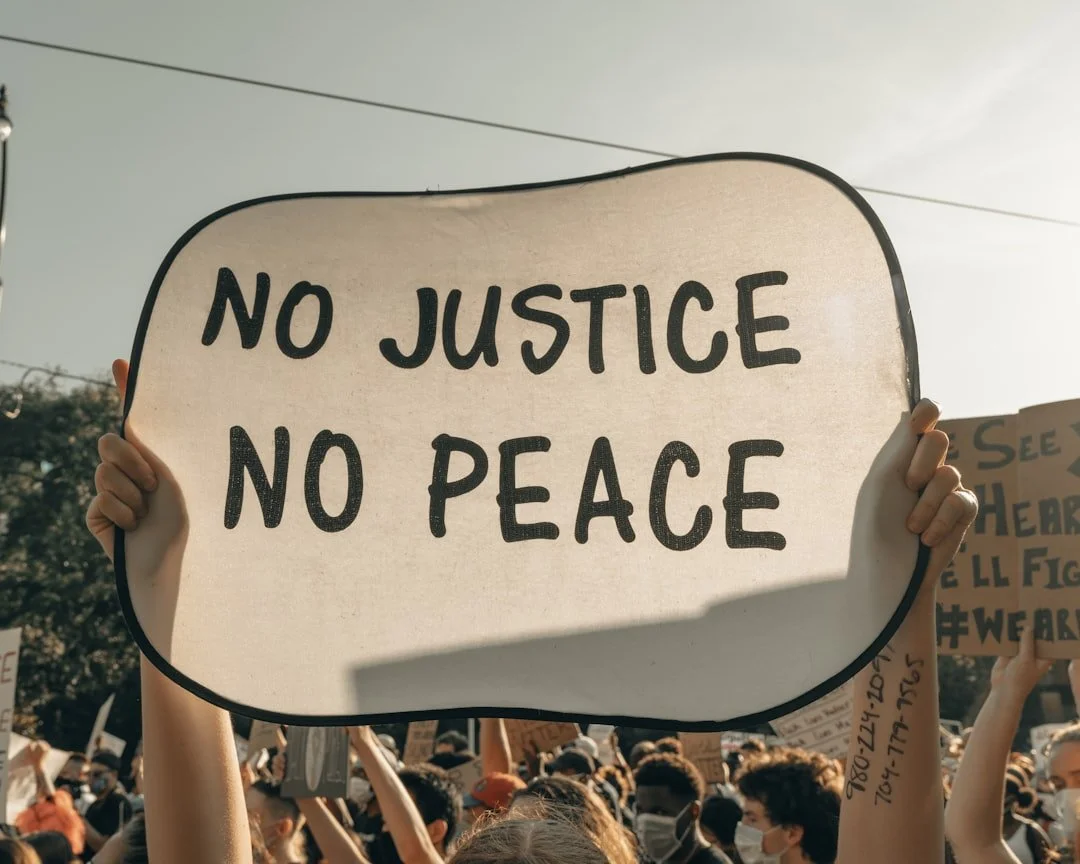

They are not progressive but regressive, looking back for inspiration to decades and centuries of patriarchy, military and economic imperialism, Christian empire, racial and ethnic bigotry, and the oppression of women and LGBTQ+ citizens. From these backward-looking convictions they seek to design and build a very different American future than one that bends toward justice.

Rather than rant on about their alien vision, I’ve been thinking about my own reaction to this transformative election. Why does it challenge my sense of myself as a citizen? My unwelcomed but unavoidable first response is that this election challenges my long-held assumptions about my personal power. When, after seeing The Butler, I responded to my wife that On every one of those issue, we were (and more importantly I was) on the right side, it was an admission that I gained a sense of personal importance that I’m finding difficult to release.

A student anti-war protest at the University of Wisconsin (via PBS)

I remember an incident in the late 1960s when I told the senior pastor I worked for that I couldn’t attend the following evening’s meeting of the congregation’s governing board because I would be at an anti-war moratorium gathering at USC. He stared at me as if I’d lost my mind, or certainly my sense of professional responsibility. Surely the evening's church business was more important than one more march for peace. I walked away feeling self-righteous about my act of courage. I congratulated myself for being on the right side about the war in Vietnam and for being sufficiently courageous to exercise my choice to be at the demonstration. I thought of myself as a person of significance.

Though I still believe we were on the correct, progressive side of these issues, I realize in retrospect that I NEEDED to be right to validate my sense of myself as a wise and just person. I NEEDED to be right to feel gratified about the time and effort I’d devoted to these issues. I NEEDED to be right to justify my pride over against friends and others who were, from my perspective, wrong. And perhaps as much as anything, I NEEDED to be right to carry on my hope that progressive views on issues of justice not only prevailed in the past but will prevail in the future, insuring the lasting impact of my efforts. I NEEDED these successes to assure myself that even in public circumstances I was a powerful person.

In my involvement in racial justice, women’s rights, and gay rights I was using my voice and my pedigree as a straight white male – a representative of the dominant class – to help work towards justice for those with less leverage than I had. Though I wasn’t conscious of it at the time, in hindsight I see a blend of both genuine commitment to principles and arrogance. I suspect that through those years, I needed this view of myself and my involvement to certify that I was indispensable. It wasn’t a long leap to believe that our pre-Baby-Boomer War Baby generation (I was born in 1941) was equally indispensable to the social battles and victories that emerged after the World War Two troops came home.

Thanks to God and the forgiveness of my peers, over the decades I’ve shed this sense of saviorism along with my view of myself as uniquely significant. I also know now there is a dramatic difference between relieving certain forms of oppression and obtaining genuine liberation. Such true freedom and equality are the goal we never get to, but which holds itself out as the north star toward which each generation hopes to move toward in small and sometimes not so small steps. But we ain’t there yet, as any clear-eyed assessment of the injustices and political and economic disparities in our culture quickly establish. The journey toward justice is a long and winding road, through the best and the worst of times. I did my part with my generation, but we didn’t finish the job on a single issue of social justice.

I now know that others are imagining a future I never envisioned, developing strategies that never dawned on me or my peers, and leading whatever protest or march I was once out in front of. In all these current justice movements I now know myself to be a supporting person: available if called upon, but no longer in charge. I need to get out of my own way as I step into the future. I need to trust diverse generations, like those of my children and grandchildren, to lead. If I can be of help, ask me. But I no longer believe the progressive movement cannot get along without me. Tell me what to do, or what not to do, as you forge a new strategy to bend history’s current arc toward forms of justice I’ve never imagined.