I’ve been thinking about men, marriage, and midlife divorce.

Hi, I’m Rick Thyne and I’m grateful that you found your way to these pages. Perhaps in these conversations we’ll find our way to more of the common good that is - for me - our best hope for a future in which all of us thrive. If you've found this column and would like to get my latest column delivered, free, to your inbox every two weeks, you can subscribe at the bottom of this page.

I've been thinking about men, marriage, and midlife divorce.

Differing studies tells us that women initiate divorce somewhere between sixty and eighty percent of the time. I've worked with several men in these situations who were caught off guard by their wives' decision to end their marriages. And while women have their own stories to tell about divorce, I'd like to focus for now on a story I've heard from many men.

In the tumult of raising two teenaged daughters, one of whom lived on the edge of each next new teen disaster (alcohol, drugs, truancy), Guy #1’s wife disagreed when he did set boundaries for their daughter, and criticized him for what she called profligate spending as he built his enormously successful business. No infidelity, no substance abuse, no physical abuse or intimidation. Just this nagging conflict between them that went on for too many years, until his wife announced that she wanted a divorce after twenty-five years of marriage. At her insistence, he moved out but stayed very close to his children and agreed to a generous financial settlement. He now lives by himself.

At forty, Guy#2 married a woman ten years younger and dove in to a decade of the pleasure of helping to raise their three children and managing his thriving international business. Twenty years into the marriage, after a decade of increasing marital dissatisfaction, she told him he’d betrayed her once too often by siding with their middle child in one of her constant arguments with their older son. She moved from their bedroom to the bedroom their daughter abandoned when she left for college. Again, no infidelity, no substance abuse, no physical threats. He’s still very involved with the two sons who remain at home, still guides his thriving business, but sleeps alone every night.

In his early fifties, Guy#3 has been looking for a house to buy because his wife of more than two decades recently announced, I don’t love you anymore, I want a divorce, but I want to stay in the house. Again, no infidelity, no substance abuse, no physical threats. Things had been stale between them for a decade, but he figured they’d wait it out until the kids were both out of the house then travel again and, hopefully, fall in love again and spend their lives with one another. She says she’s long past considering such a reconciliation. She’s been pushing him to find another place to live.

When thinking about these and other men whose wives are leaving them, I found myself meditating on this from the opening of Dante's Inferno:

In the middle of the journey of our life, I came to myself, in a dark wood, where the direct way was lost. [Dante, Inferno, Canto I]

Somewhere between their twenties and their forties, the direct way was lost for these men. What happened to them? How did they wind up alone in midlife? And what should these men do now?

What men surely should NOT do is what too many do: quickly replace their departing partner with a new one. Men hate to be alone, something women seem to have greater tolerance for. So, as the therapeutic cliché has it, Women grieve while men replace. But until men process what happened in their failed marriages, they’ll simply repeat their mistakes in a new one. Which is why second and third marriages fail at a greater rate than first marriages.

Dante’s phrase, I came to myself, points to a wiser response for men. It is time to make an honest assessment: What happened to me? Whatever her part in this divorce, what was my part? And what do I do now to make my next relationship more enduring? Again, Dante leads the way with the second sentence of the same quote from his Inferno: It is a hard thing to speak of, how wild, harsh and impenetrable that wood was, so that thinking of it recreates the fear.

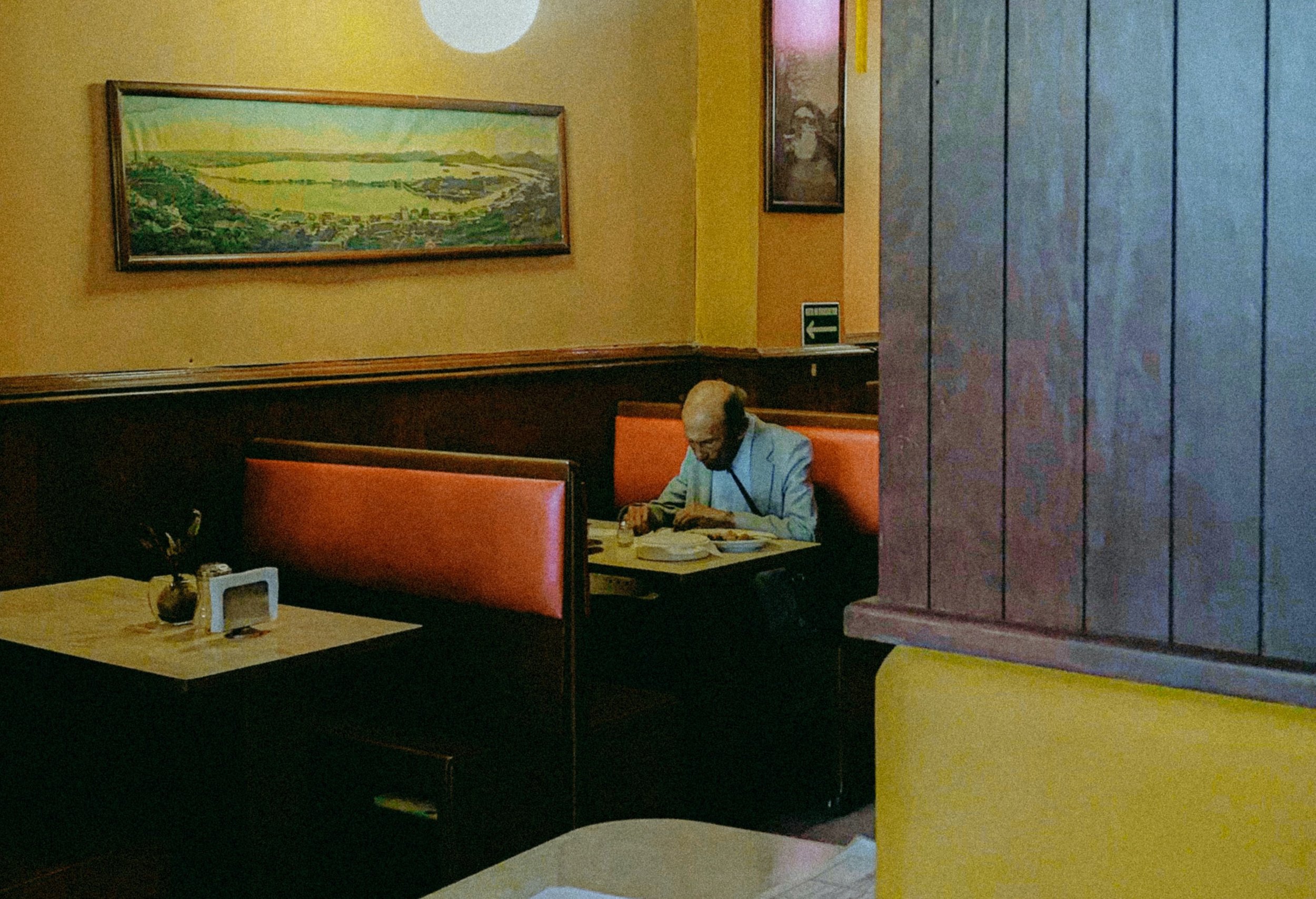

Acknowledging how frightening this new circumstance is may lead men to the inner world they have neglected. When you’ve known the comfort and safety of even a so-so marriage, it’s terrifying to be alone, to sleep with no one’s head on the pillow beside you. And the death of the family, however amicable the separation, is profoundly sad: Wednesday dinners and every other weekend hardly replace the years around the same table, vacations together at the same beach or cabin, celebrations together of birthdays and holidays. Fear. Sadness. And that terrible sense of vulnerability when you realize there may not be another relationship out in front of you, certainly not one like the one you’re leaving behind.

In the best of circumstances, the self-exploration that divorce provides means discovering segments of your humanity the culture has not encouraged for men: emotional and spiritual mysteries, deeply profound loving relationships, a soulfulness that is empowering. It is the opportunity to find our way in the dark wood and to discover parts of ourselves we've never known.