I've been thinking about how I finally learned to read.

There was a wonder I experienced when my mother read to me as a child – Pecos Bill was a cowboy out in the wild, wild west. He lived with his father and mother and sixteen brothers and sisters in a little log cabin in Texas – I could envision myself wedged among those sleeping siblings, pricking my finger on a tumbleweed, closing my eyes against the wind-blown dust.

Neither of my parents finished high school, caught as they were in the depths of the Great Depression and grateful for whatever work they could find. My mother plucked chickens, then taught herself enough secretarial skills to find work between giving birth to five children.

In his thirties, my father hitchhiked from Lowell, Massachusetts to Hollywood just before the US entered World War Two, married my mother whom he met in the boarding house they lived in when she was twenty-eight years old, went to work for his brother who owned a newsstand on Hollywood Boulevard. They sold several daily newspapers, magazines (I saw Marilyn Monroe on red velvet in the initial issue of Playboy when I was ten years old), comic books and tip sheets for handicapping horse races across the country. He bought the stand when his brother married and moved to Rochester, New York.

BECOME A FREE SUBSCRIBER TO I’VE BEEN THINKING

It wasn’t until I got to college that I realized I wanted something more out of life than they were able to cobble together and that I had a lot of educational ground to make up. After two years at a state college, I got an undergraduate degree in history and English literature from UCLA, earned two master’s degrees in theology at Princeton Theological Seminary, then in my forties earned another master’s degree, this one in psychology.

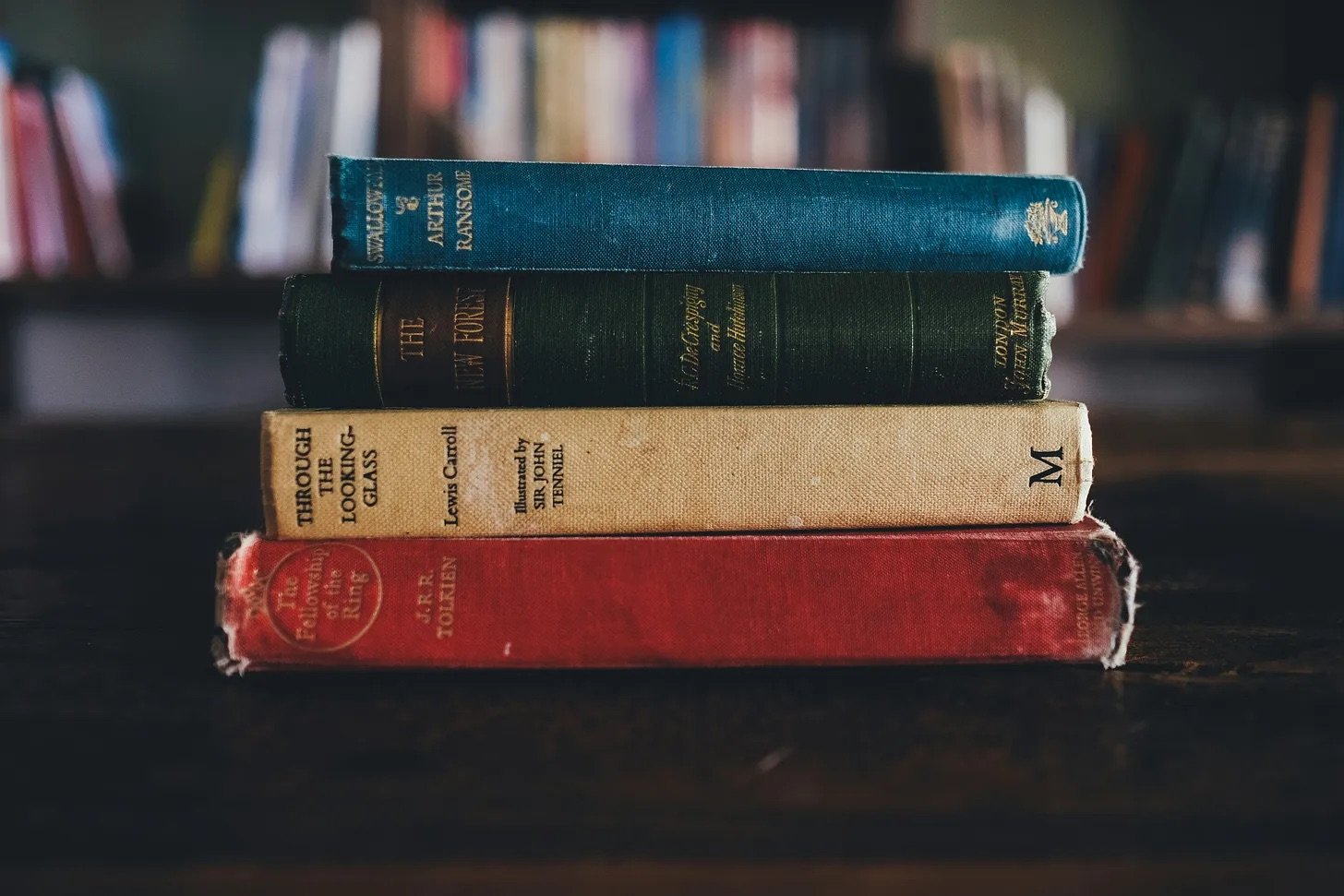

Through it all I read like a madman, so sure that if I didn’t get to every important book, someone would ask me a question about it and expose the gapping intellectual deficit (you know, that imposter syndrome) that I feared lay just beneath the surface of my academic credentials.

In school I read to be able to talk and write intelligently to prove that, unlike my parents, I was well educated. When I became a pastor, I read to find stories or examples that I could turn into a sermon’s lesson.

What do The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn teach us about our nation’s history of race, and what are the lessons to be learned from that story about our current racial tensions?

My unspoken but constant personal effort was to come across as original, to say and write even on familiar themes in ways that had a different, surprising twist to them. I wanted to be noticed as a truly creative thinker.

A friend recently pointed me to Ursula K. Le Guin’s collection of essays, The Language of the Night, where I found her brief article, “Why Are Americans Afraid of Dragons?”

Dragons, writes LeGuin, represent the vast world of imagination, fantasy, science fiction, with an emphasis on storytelling that is the soul of fiction but only an element of non-fiction, which is more concerned with sharing information. She suggests that many people read nonfiction to learn something new or to improve themselves; some don’t have interest in or time for made-up narratives and the complex interplay of fiction’s characters.

To discover the richest treasures in fiction’s stories I had to set aside my search for the lesson and consider realities that could be found only in the niches of my imagination. I had to pry myself free from my intellectualism, my need to learn something useful, and read about dragons and unicorns, Hobbits and space aliens, and a story about a boy on a raft with a runaway slave floating down the great brown God of a river.

It took me until I was in my forties to stop worrying so much about the lesson and whether people thought I was smart. I opened my imagination to whatever new world the author laid out before me and set myself loose to wander with fresh eyes and ears, brand new senses of touch and smell. I started to experiment with questions like

What choice would I make if I were in this situation? What would I feel in these circumstances? What if I were this character and not who I am, a woman in her circumstances and not a man in my own?

Huckleberry Finn is indeed about race, as a run-away twelve-year-old white boy and a runaway Black slave old enough to have a wife and a daughter seek their freedom on this river that bisects free states from slave states. The lesson might be about their desire for freedom, the powers that oppose it, or the treacherous journey of those who would risk it. But beyond the lesson is a story about a boy who runs away from home because his father abuses him, and a man who can no longer stand the humiliation and abuse he, his wife and his daughter experience every day. They both run away, choosing to risk their lives rather than enduring one more day of this abuse.

In March 2024, Percival Everett, an African American writer, published James, a novel which re-tells Huckleberry Finn from the slave Jim’s point of view. Everett exercised his writer’s freedom to re-define Jim from the beginning of the story. Yes, he was a slave throughout, but we learn early on that he’s spent years sneaking into the plantation library, teaching himself to read, and steeping himself in classic literature. His education is the core of his redefinition from the uneducated slave, Jim, to the erudite Black man, James.

Knowing this, we find him back on the river with Huck, enraged and terror-filled by the slavery that still lingers in him as it does in the souls of so many Black people who are his heirs. It’s the Black skin white people like me don’t want to climb into, but which Jim’s/James’ story invites us to dare to inhabit.

In a way I hadn’t felt before, James helped me understand the rage toward me as a white man that still resides in people of color whose historic families were enslaved, distained, and tyrannized by my historic families, and whose current Black families still feel the whiplash of racist disdain.

Huckleberry Finn and James invite me into an experience open to me every time I read a piece of fiction. I have the choice not just to find whatever lesson the story offers up but to inhabit a new world, to try on a different skin, to step out of the comfort of my own life into the danger and humiliation and terror and triumph of another human being.

My father hit me as a boy, though not with Huck’s father’s violence - how does this influence the way I read Huck's tale? My reaction to being hit as a child was to vow never to raise a hand to my own children or grandchildren. But as a pastor and therapist for fifty-eight years, I know that not all abused children grow up to be non-abusive parents. What if the threat to me from my dad or from other kids and adults had increased? Would I have run away?

Can I climb into Jim’s skin, into the humiliation and cruelty, the denial of my humanity, the robbing of all my rights to dignity and intellectual and cultural freedom that slavery entails? Can I imagine myself so miserable that I would abandon my wife and child, entrust my life to a twelve-year-old white kid on a raft on the deadly river?

Those for whom fiction seems unproductive cannot imagine what these made-up characters in their made-up circumstances could possibly teach us about acknowledging the unspeakable in our own families, in our wider culture, on the job or in our church or among out friends. We close our eyes, put our fingers in our ears, deafen ourselves with our loud La La Las rather than consider what these fictional characters could possibly teach us, not about them but about us. How will a raft and a river reconstruct my vision of where I’m headed in life and who I’m travelling with?

Fiction is not escapism, not a waste of precious time that could be better spent accumulating more knowledge or honing my skills. Fiction is an invitation not just to float down a river but to do so as an abused boy or a battered slave. Fiction offers up other worlds for me to explore and in so doing permits me to reinvent myself as I allow my imagination to wander into unknown territories.

What if I lived in this different world? What if I were a different person? What if I gave up my privilege and lived in distress?

To finally learn how to read gives me an opportunity to find new explanations for who I am and why I’m here. Or, as Le Guin puts it, fiction invites me to face my fear of dragons and unicorns, Hobbits and the space aliens of science fiction. It challenges me to step into an unfamiliar and potentially dangerous new world.