I’ve been thinking about walking on eggshells.

BY RICK THYNE

After seeing Sandra for several years, I suggested that she perhaps had a small role to play in the most recent marital dispute with her husband, a suggestion of her responsibility that I’d never dared raise with her in the three years I’d been seeing her. She nodded slowly but said nothing. I talked on for about ten minutes with only perfunctory responses from her. Then Sandra looked at me fiercely, said, You just don’t get it, do you? You never do. She stood up, and as she walked toward the office door she said, I’m through with therapy. She never returned.

In a one-hour therapy session with clients like Sandra, their emotional responses are all over the place. They move from moments of adoration and trust – you’ve made this the only safe relationship I have in my life – to deep disappointment – why is it you never understand me when I tell you about my asshole partner – to anger – if you as much as hint that you think I’m wrong about this, I’m done with you. These changes usually occur without apparent provocation, come on with an unexpected urgency, then usually dissipate as the next emotion rushes in.

Sandra suffered from Borderline Personality Disorder which is a serious, disruptive psychological problem whose origins we are not yet certain of. For decades, we thought it came from unconscious and therefore unacknowledged childhood trauma, but recent research suggests that it may have genetic origins. Whatever its source, the best metaphor I ever heard to describe the disorder is as if a person lives in an emotional body without a skeletal structure.

With no steady, consistent sense of who they are, they’re at the whim of whichever emotion in them is most urgent in the moment. They’re terrified of abandonment, so they interpret any notion of their responsibility for the pain in their lives as a fundamental betrayal of the bond between us, and find ways to express their rage, either verbally or by consistently keeping their distance. These powerful dynamics make it difficult for people with this disorder to maintain stable, satisfying relationships. They don’t trust partners, parents, children, friends, or therapists, and they make it difficult for others to count on them.

No wonder one of the most popular studies of what it’s like to live with someone who has this disorder is titled WALKING ON EGGSHELLS. You never know who’s going to show up at the breakfast table or at the social gathering you’re headed for. If you’re the child of someone with Borderline Personality Disorder, you never know who’s going to be there when you get home from school - perhaps you discover your belongings on the front lawn in response to a perceived incident of "disrespect" at the breakfast table.

Though I deal with this issue every week as a therapist, either with people with this disorder or with their family members, I've increasingly noticed how I'm also walking on eggshells with certain friends and acquaintances about hot-button public issues. I’ve lived most of my life with friends and family members who disagree about religion or gender issues, about war and peace, or who come from differing sides of political issues. In the past, we could be comfortably safe with one another despite such disagreements. But things have changed.

Now, if we disagree, it’s not just about conflicting perspectives. Now, if we’re not on the same side, we’re often seen as enemies. I cannot be trusted. Your opinions do not deserve respect. And if we persist in disagreements, these relationships are quickly in jeopardy. It's as if our entire culture has succumbed to Borderline features. With all this confusion and conflict, we’ve lost our sense of who we are; we no longer identify ourselves as E Pluribus Unum, Out of Many, One, or One nation, indivisible.

Now, if we’re not on the same side, we’re often seen as enemies. I cannot be trusted. Your opinions do not deserve respect. And if we persist, these relationships are quickly in jeopardy.

And we’re full of rage: how dare the other side challenge our view of reality. We feel abandoned by disagreeing family and friends, even our most dearly beloveds. So when we’re in conversations where these differences occur, we wind up walking on eggshells, which exacerbates a distance that didn’t used to be there.

I had early warnings years ago about this breakdown in our sense of community when I read Philip Slater’s 1970 book, The Pursuit of Loneliness: American Culture at the Breaking Point, and Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone, in 2000. Both books catalogued the increasing isolation that was creeping into American life and has since become epidemic: the decline in neighborliness, the increasing dissolution of families, more mobile career paths, the decline of religious communities, the profound increase in racial, religious, and ethnic diversity, and the ubiquity of social media with its emptying out of the meaning of friends.

If a person with Borderline Personality Disorder lives in an emotional body without a skeletal structure, it feels increasingly as if we also live in a political and cultural body without a skeletal structure. All the community structures that once articulated us together and demanded a certain level of mutual accommodation and respect - Elks' Clubs, neighborhood associations, churches, bowling leagues - have either disintegrated or are in sharp decline. Furthermore, it's entirely possible now to opt out of community structures entirely, and to exist in an echo chamber of media and views that only confirm your existing beliefs about the world.

If a person with Borderline Personality Disorder lives in an emotional body without a skeletal structure, it feels increasingly as if we also live in a political and cultural body without a skeletal structure.

Our family has not escaped this experience of more and more distance from our neighbors and friends. When our now fifty-something children were little, we lived on a cul-de-sac of twelve homes, four of which were occupied by young couples with kids around the same age as our kids. On pleasant evenings, we rolled a Weber portable barbeque up and down the sidewalk to share dinner together at whichever of the family homes our kids we currently playing together. For three years, we created and thrived in our only experience of neighborhood. We were neighbors then and are dear friends over fifty years later with one of those couples.

Now, in our eighties, we’ve lived in the same condominium complex for twenty-four years and exchanged dinner dates once with only one couple out of our twenty neighbors, the couple next door who moved to Florida twelve years ago. I’m not aware whether anyone else in our complex is part of a religious community, or part of a service organization. I assume that, like us, everyone around us is on social media and has dozens of on-line friends; but we exchange little more than waves as we pass each other leaving or arriving in our cars. I’m ashamed to admit that other those two shared dinners, I’ve never been in a conversation with any of my neighbors that lasted more than ten minutes. In twenty-four years.

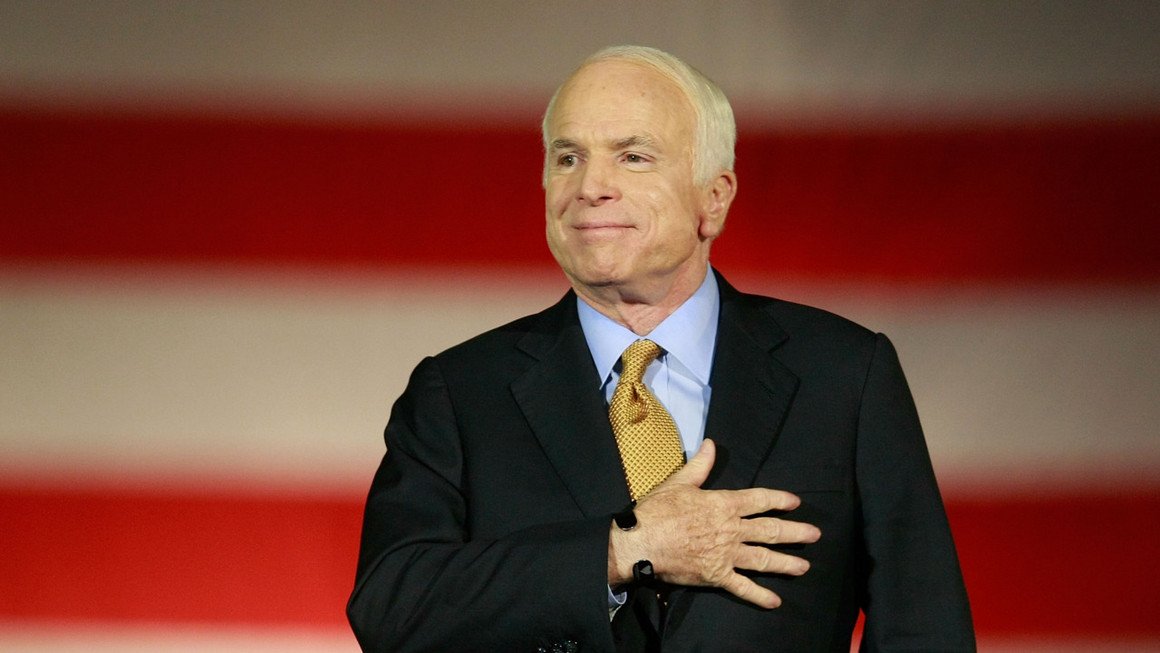

In 2008, this is what John McCain said in his concession speech (remember when losers made concession speeches?) the night Barack Obama defeated him in their presidential contest:

I urge all Americans who supported me to join me in not just congratulating him, but offering our next president our goodwill and earnest effort to find ways to come together, to find the necessary compromises, to bridge our differences and help restore our prosperity, defend our security in a dangerous world, and leave our children and grandchildren a stronger, better country than we inherited. . .

Tonight — tonight, more than any night, I hold in my heart nothing but love for this country and for all its citizens, whether they supported me or Sen. Obama. I wish Godspeed to the man who was my former opponent and will be my president.

Such public grace seems unimaginable now. We’re not just opponents; we’re enemies. And any form of cooperation with the other side is seen as betrayal, which causes us to rage at one another. So, like those in relationships with people who suffer from Borderline Personality Disorder, we find ourselves walking on eggshells, careful about what we say or do even around people whom we’ve cared about for decades.

If our current cultural breakdown of community is in fact the same sort of public character disorder that borderline personality is in individuals, we’re in for a long-term recovery. One of the official diagnostic manuals of emotional pathologies describes personality disorders as indelible and maladaptive, which means they are deeply embedded and disabling. Could this be so of our current public disorder?

I’m not an optimist. I’ve lived through too much personal and public darkness to think the sun will magically come out tomorrow morning. Dark moods, whether personal or public, have staying power. But I am my own kind of hopeful person. I believe it is possible to rise every morning, and even in the darkness, to put our left foot in front of our right foot.

I’ve seen people with Borderline Personality Disorder find solid ground, an emotional skeletal structure on which to build meaningful relationships and functional careers. It takes a long time and relentless hard work, but it happens. I’ve watched people slowly make their way out of crushing grief, disabling depression, moral bankruptcy, bitter conflicts, and whatever else life’s cruelty throws at us, and make their long, steady way to emerging light. Humanity has made its way through millennia of division, war, suffering, and disease by driving ourselves forward, doing whatever hard work it took to recover from these disasters and create a community of citizens who made our way together. Perhaps we will choose to do it again - and in the meantime, I am going to talk with some of my neighbors.

Thanks for reading I’ve Been Thinking. This post is public, so if you enjoyed it, please feel free to share it with a friend!