I've been thinking about books that mattered to me this year.

I don’t see therapy clients between Christmas Day and New Year’s Day, but I use the week to clean up those piles that accumulate, unattended to, during the year.

One major task is to figure out where to store the books that are in three stacks on the counter near my bed; there’s room for a few on book shelves if I slide them in on top of the orderly rows, some I will give away, and a few that I just might read or skim through again will go back on the bedside counter.

While sifting and sorting, I realized there were a few books from this year that stick with me and which I want to share with you in case the piles on your counter have diminished and you need something to read to begin the new year.

The Inferno

By Dante Alighieri; translated by Robert and Jean Hollander.

For Christmas last year, a friend gave me a copy of this, which I surely should have read earlier. I spent most of January descending through the nine circles of Hell, each one both physically and emotionally more brutal than the one we’ve just survived. A few impressions linger.

As Robert Hollander writes in his introduction,

Reading Dante is like listening to Bach.

There is a grandeur in the language, the poetic meter, the themes, and the sheer beauty of the writing. Also, there is the earthiness of the contemporary politics of Dante’s world (he was born in Florence in 1265 and died in Ravenna in 1321); he weaves into this narrative of Hell names and conflicting parties he was personally and politically involved with. Finally, there is the theology.

What I find most compelling in The Inferno is Dante’s understanding of the complexities in each of us, those aspirations that elevate us and the inevitable inner demons that drag us toward the Devil. Dante has provided the complete catalogue of sins that undo us and, in his imagination, lead the unfaithful to their damnation.

Between them, Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling and Dante’s horrifying poem provide the visions of Creation and Hell that are the backdrop of Western Christianity’s images of these eternal realities. I grew up as a Christian with these beliefs about God and sin and Heaven and Hell. Alas, I no longer find this description inspiring or intimidating. The brilliance of Dante’s vision has dimmed as my own faith has moved beyond his portrayal of a cruel and vindictive God, a human family saturated with evil, and any fixed imagination about life after death.

Arn Chorn-Pond is a human rights activist working on Cambodian reconciliation efforts and the preservation of traditional Khmer music. His experiences form the core of McCormick’s book. Credit: Jocelyn Glazer, The Flute Player (2003).

Never Fall Down

By Patricia McCormick

Since our daughter entered high school forty years ago, I’ve been reading both fiction and non-fiction from my children and grandchildren’s high-school and college reading lists, and this was on my grandson's summer reading list. In McCormick’s story, eleven-year-old Arn is taken from his Cambodian home and family by the Khmer Rouge and forced to become a child soldier and ruthless murderer in the brutal 1975-1979 war.

As soon as I began reading, I remembered scenes from the 1984 movie, The Killing Fields, with its gruesome depiction of detention camps, mass torture, and death. But no one could possibly put on film what Arn becomes party to: killing other prisoners in brutal, horrific fashion, staying alive by obeying hideous orders to expose and murder anyone who dares question the atrocities, and wandering through the decomposing killing fields searching for what might remain of his family.

Though this true story actually has a redemptive conclusion, this hopeful note is overwhelmed by the continuous malignancy in the character of these terrorists and the unspeakable horrors of war that are indelible. It reminds me that, caught up in a righteous cause, we are capable of despicable horror. Surely for a high school junior this was a grim introduction to a world I pray he never has to experience close up.

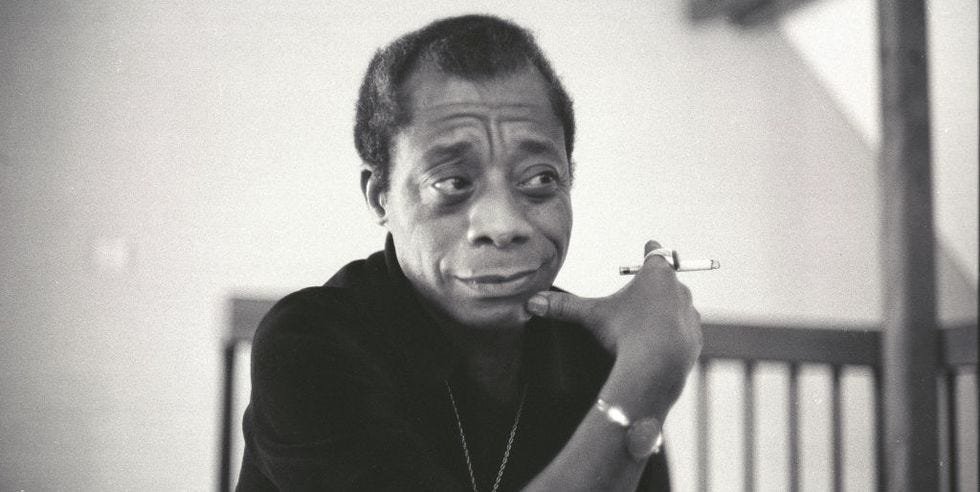

Credit: Sophie Bassouls - Getty Images

The Fire Next Time

By James Baldwin

This is another one from my high school grandson's reading list, but also an old friend. It is still thrilling to read this 1962 letter from Baldwin to his nephew, which is the model for Ta-Nehisi Coates’s gripping, more contemporary 2015 letter to his son, Between the World and Me, which updates Baldwin’s doubt that white people will ever own up to and correct what we’ve done to Black Americans.

As in all of his fiction and nonfiction, Baldwin pulls no punches, either about what’s happening to Black people in America or what he thinks of white people and certain Black leaders; he includes here an extensive description of his relationship with Elijah Muhammad, the head of America’s Black Muslims who killed their former spellbinding prophet, Malcolm X. In the midst of his rage, he finds the grace to acknowledge what he knows are his own foibles.

I was initially surprised when this book turned up on the junior-year reading list, since it’s been sixty years since it was published. And I must admit I find it personally disturbing when both Baldwin and Coates express their lack of hope that white Americans will ever come to terms with our racial history. Their hopelessness leaves me feeling disenfranchised from the conversation, like nothing I’ve done about this mattered and I have nothing more to say or nothing more to do that will enhance the experience of Black Americans.

But of course, Baldwin and Coates’s point is to disturb me, to make me rethink whether or where I belong in the conversation. Perhaps this disturbance and my subsequent rethinking are why I’m grateful for James Baldwin every time I meet up with him.

Our Kind of People

By Carol Wallace

I’ve known Carol and her husband, Rick Hamlin, since they became a couple in college forty years ago, and I’ve read most of their copious output of fiction and non-fiction. I’m sure my reactions to their writing refract through the prism of my love for them, which influences my reading of every page. Still, I really like this, Carol’s most recent novel. She has a deep attachment to the Gilded Age in New York City, where she and Rick have lived and raised their children since they graduated from Princeton in the 1970s.

This is the story of Helen Wilcox, whose husband’s daring business dealings have her dangling on the edge of the upper crust as she lobbies for her daughters’ invitations to the right parties and perhaps an offer of marriage from a proper young gentleman. The characters are anything but stereotypes, each of them with particular eccentricities that add color to their considerable virtues.

I never watched Downton Abbey, which was inspired by Carol’s earlier book, To Marry an English Lord, but if it’s anything like Our Kind of People, I just might get around to it, as everyone else seems to have done.

Dr. Jennifer Doudna in Berkeley, Calif., on Jan. 18, 2019. Credit: Anastasiia Sapon—The New York Times/Redux

The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race

By Walter Isaacson

I was very close to two gay men who invited me and my wife into their social and political worlds in the 1970s, before the AIDS plague began its lethal march through the U.S. in 1981. In 1987, Randy Shilts, a San Francisco Chronicle journalist, published the then-definitive story of the epidemic in his book, And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic, which was made into an equally brilliant television docudrama in 1993. Near the center of that story were two competing laboratories, one in Paris and the other in the U.S., each trying to identify the virus that was causing AIDS.

Because we’ve witnessed the success of our efforts to define, treat, and now cure AIDS, there’s reason to hope that we might accomplish the same with what we know will be new forms of the virus we’ve spent the past three years battling.

Isaacson lays out a history of research on bacteria that led to a competition, much like the AIDS virus competition decades before, between Jennifer Doudna’s lab and other competing labs for breakthroughs that led to CRISPR, a gene editing tool that eventually could detect and destroy the coronavirus. Early in the recent pandemic, Doudna and her collaborator, Emmanuelle Charpentier, were awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their discovery.

I’m not a scientist and cannot remember ever taking a chemistry class in school, but I found this book very accessible and completely captivating. Isaacson describes each of the main characters in this scientific search in both personal and professional ways, catalogues their equally competitive and collaborative projects, and leaves me with wonder at what these researchers do and how they might influence the future of the human race.

A Prayer for Owen Meany

By John Irving

Becky and I have been reading mostly twentieth-century American fiction for the past fifteen years with a group of friends and recently went looking for something we might have missed from earlier decades. Guess who we found? Not only John Irving, but perhaps his greatest character, Owen Meany.

Our group is not meeting again until February but, having read it twice before years ago, I couldn’t wait. I set aside the stack of next-in-line books, and wondered if Owen would hold up after the decade or two since we last visited. I teared up by the end of this opening sentence:

I am doomed to remember a boy with a wrecked voice – not because of his voice, or because he was the smallest person I ever knew, or even because he was the instrument of my mother’s death, but because he is the reason I believe in God.

I was all in after that.

I’m purposefully taking my time, savoring events I remember but now feast upon again, looking forward to finding an hour here or there to shut out the ordinary and slip into this extraordinary world, this extraordinary character, this extraordinary story that Irving rolls out without hurry. If you’ve never met him, it is my honor and pleasure to introduce you to Owen Meany.