I've been thinking about bodies and shame.

Until adolescence turned it into a danger zone, I seldom paid any attention to my body. I just let it do whatever a young boy’s body wanted to do. I ran with my friends through the neighborhood, wrestled with my cousins, played kick ball at school and rode our bikes until dusk through the streets of Burbank and all the way up to the quarry, unsupervised.

I stuffed my growing body with foods I loved without a thought about calories, cholesterol, or my general well-being: Wheaties with whole milk for breakfast, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on Wonder Bread for lunch (more milk), always meat and potatoes at my Irish father’s dinner table, and nightly dessert, usually rocky road ice cream. After weekend baseball games in the vacant lot across the street, I scraped up enough allowance money to walk to Sailor’s liquor store at the end of the block to buy a quart of Par-T-Pak Cherry soda and a Hostess Cupcake. My delighted body thrived on what then were my basic food groups.

Every day a happy body, every day a happy boy. I slept like a baby.

When hormones hit when I was thirteen, I discovered other pleasures my body could provide. My new and intense desire was to stare at and wonder about being close to these girls who sat beside me in class and walked the school’s hallways apparently unaware of the torturous conflicts they aroused in me and my friends, these exploding fantasies of what I might discover if I got close to them. Immediately upon experiencing these eruptive desires, I ran smack into loud and clear warning signs from the church youth group I was part of and the culture around me: Slow Down. Stop. Do Not Enter.

And for the first time I was caught in what became this life-long tug-of-war between my sensual, embodied self and the controlled self I was told to be. This intense awareness of my body’s desires immediately introduced me to the shame that’s inhabited my conscience ever since.

From Charles Atlas to instructional films like this 1954 classic entitled “Habit Patterns” (wherein a narrator criticizes every choice a teenage girl makes for fourteen long minutes), there was plenty of shame to go around!

I know I wasn’t alone then, any more than I’m alone now. Among my current, aging friends are women who were not allowed to wear bathing suits as teenagers, and who dressed (often under their mother’s watchful eye) to drape whatever might be evident under tighter fitting skirts and sweaters. Men friends were told, as I was, that even wet dreams were unacceptable (as if any of us can control our dreams!), and Charles Atlas’s magazine ads scolded kids like me for being 98-pound weaklings and warned that if we didn’t sign up and pump up our skinny limbs, muscular bullies would shame us in front of our girlfriends by kicking sand in our faces at the beach. Opportunities for shame were suddenly as plentiful as my curious fantasies.

Opportunities for shame were suddenly as plentiful as my curious fantasies.

Conventional wisdom laid out the proper course for managing my body’s desires: stay chaste until marriage (oops!), marry the person of your dreams (got that one right), eventually have 2.5 children (we wound up with three), and remain faithful till death do us part (hmmm!). Given this road map, my assumption was that the conflict between desire and shame would disappear early in the course of our married life. But this didn’t happen. So deeply implanted was this struggle that the abrupt marital change about sexual pleasure from NO to YES didn’t erase my inclination toward shame. So I’ve spent decades trying to sort out this complicated relationship between my conscience and my sensual self. I now have less shame than I used to (though it hasn't disappeared), and more comfort with my body than I might have expected.

As I watch my adult children and three grandchildren, ages ten through seventeen, I see a different lived experience about bodies and shame than the one I had. As far as they would tell and I could figure, my kids grew up in a world different from the one I grew up in, and navigated the conflict between pleasure and conscience with more success than I had. The world in which my grandchildren are living, and which all of us have to come to terms with if we’re to help guide them through it, is not the world either I or their parents grew up in. I had an articulated moral narrative to instruct me, religious guardrails that introduced me to shame, a single model for traditional marriage to guide me.

My grandchildren have a much more complex moral narrative, few religious guardrails, and multiple models of successful relationships. In addition, they have access to the internet’s sensual garbage dump and a diverse and multicultural peer group which offer up opportunities we never imagined while growing up. Their landscape is different but no less difficult to navigate around issues of bodies and shame.

We’ve changed the script about bodily shame from when I was young, but the intent is the same: to control the way people publicly exist in their own bodies. Why? Because of a pervasive fear that any way of being that doesn’t reinforce those pre-existing scripts poses an existential threat to our traditional way of life together. But of course that’s nonsense. When society - or a very vocal minority - insists that anyone express their identities, their sexuality, and their choice of partners by a particular standard, it is a betrayal of the increasingly obvious fact that humans, like any species, express themselves with incredible and marvelous variety.

We’ve changed the script about bodily shame from when I was young, but the intent is the same: to control the way people publicly exist in their own bodies because of the pervasive fear that it’s a threat to our traditional way of life together.

The good news is that many people are making progress in coming to terms with the goodness of our bodies' longings, quirks, and individual differences. Clearly my children were more open than I was at an early age to talk about and act upon their desires, and like most of their midlife peers they are less repressed than we were. And our grandchildren are living in different relationships with their own bodies and their own choices about sensuality, and in equally different relationships with friends who are not like them.

I once expected that, at least for me, the fight between shame and my desires would be over by now. Like much of our culture, I assumed whatever fires once burned in my body would long since have turned to ash. Ah, not so! Which is why Roger Angell is a comfort to me.

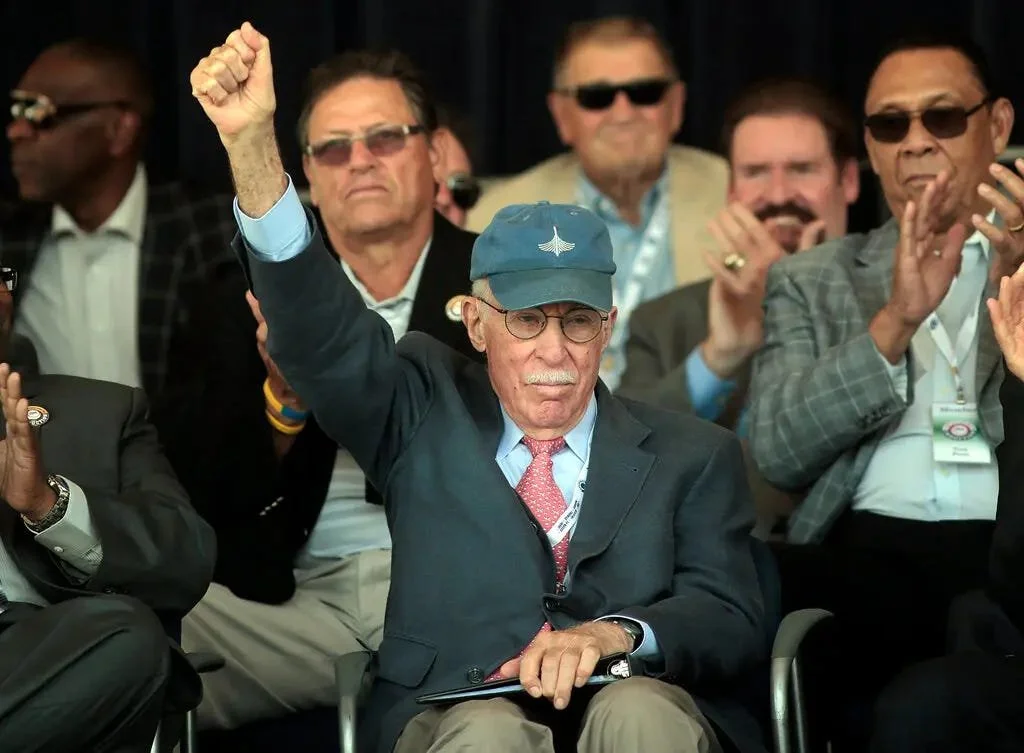

Angell in 2014 in Cooperstown, N.Y. after receiving the J. G. Taylor Spink Award, the Baseball Hall of Fame’s honor for writers. Photo Credit: Nathaniel Brooks for The New York Times

He died in 2022, when he was 101 years old. In 2014, when he was ninety-three, he wrote this in his memoir, This Old Man:

“I believe that everyone in the world wants to be with someone else tonight, together in the dark, with the sweet warmth of a hip or a foot or a bare expanse of shoulder within reach.”

Count me among this sensual tribe!