I’ve been thinking about books that have been important to me this year.

I’m a more strategic reader year after year. I no longer have any reservations when giving up on even a highly popular and well-reviewed book: I only have so much reading time left, so I want to spend it well. When I was busier in my life, I read mostly in brief spurts, sometimes ten or fifteen minutes at a time. These days, I read for an hour or two, not just touching a story but moving in to it. And I read with a pen in hand – I find that by underlining sentences or paragraphs that capture the plot line or are just too wonderfully written to ignore, I can re-read or find memorable passages in a fraction of the time.

BECOME A FREE SUBSCRIBER TO I’VE BEEN THINKING

Certain books from this past year have stuck with me, so I want to share them with you as this new year begins.

This year, I finally got around to The Parable of the Sower (1993) and The Parable of the Talents (1998), both by Octavia Butler. Butler is a brilliant and brave writer, and the combination of these two qualities made reading her a compulsion. Once I was engaged, I didn’t want to come up for air: I finished Sower, and immediately opened Talents and read to the finish. Both books share a central character: we meet Lauren Olamina on the first page of Sower as a teenager in Butler's vision of a 2024 that was then two decades in her own future. In her 2024, climate change has created a divided world with prosperous families like Olamina's living behind walls and gates, heavily armed against the desperately hungry, thirsty populous outside the gates. Olamina’s journey through this conflagration is the plot line of these two novels.

I was fascinated by this young woman whose courage, improvisational reactions to new circumstances, and refined definitions of faith are challenged for nearly a decade by the rising tide of conflict. From the early pages of Sower until the final page of Talents, Olamina faces circumstances of desperate cruelty that are surprising in their often-horrific detail, yet so compelling that I kept turning pages. In Talents, which begins in 2032, Olamina has created and settled into a peaceful, rural community with other surviving outcasts, committed to a common life of shared goods and peaceful interactions. When they run afoul of the dominant urban culture who see their values as treacherous, they are attacked, scattered, and forced to live out their once common values in a hostile world without their community.

Olamina's great irony is to have once lived in the protected class behind gates and walls and to end up among the marginalized she once had to protect herself from. The parallels to so many current conflicts between the privileged and the marginalized are eerie: even if this version of 2024 isn't exactly ours, it's close enough to be deeply uncomfortable. There is a constant brilliance to Butler’s writing, and Lauren Olamina now lives in that village in my mind inhabited by unforgettable literary characters like Ulysses, David Copperfield, and F. Scott Fitzgerald's legendary Daisy Buchanan.

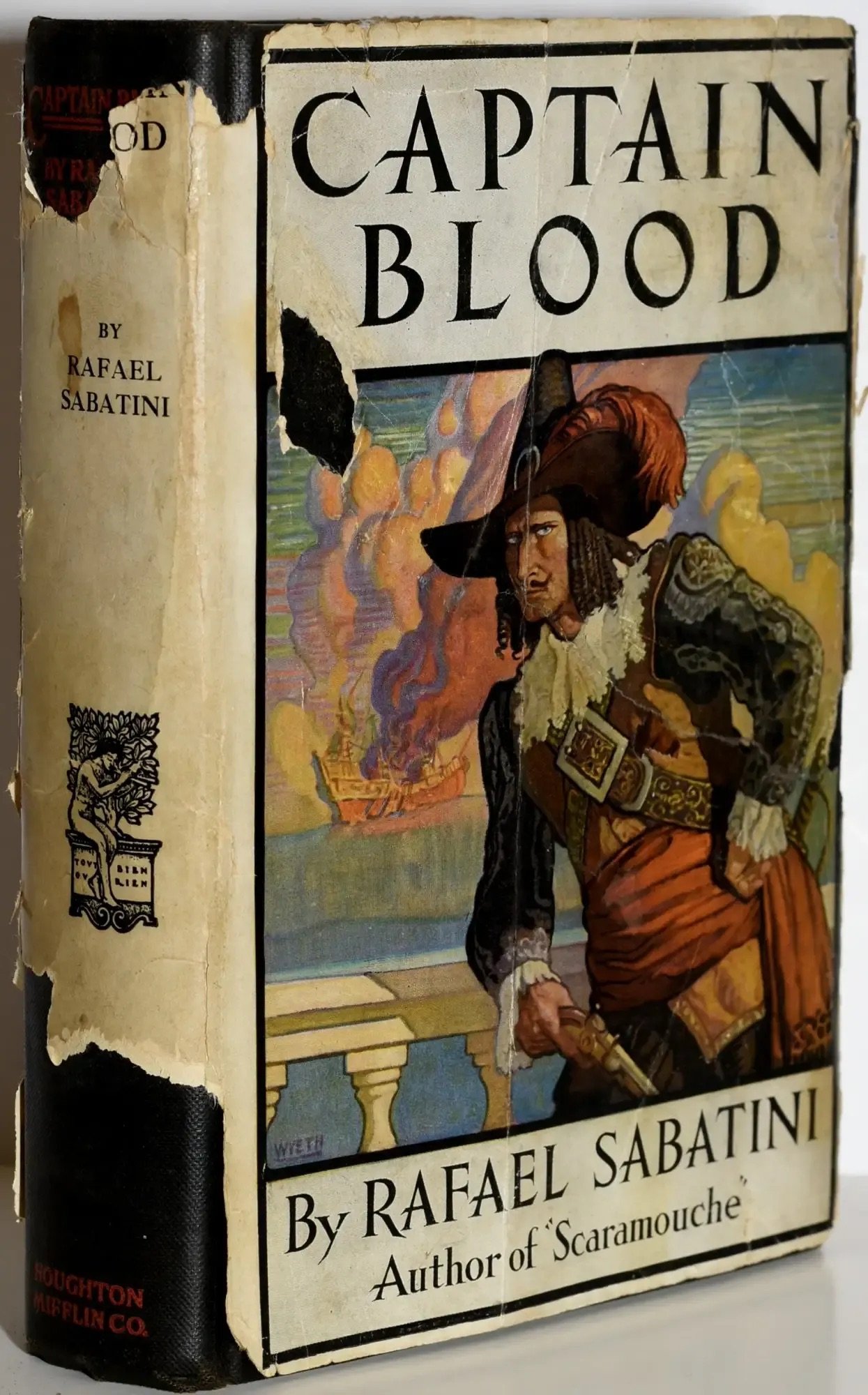

When our book group decided to read David Grann’s 2023 best seller, The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny, and Murder, on a lark we added as a companion piece Captain Blood, a 1922 novel by Rafael Sabatini. The Wager was fine but Captain Blood was a memorable high-octane thrill. The story was turned into a film with Erroll Flynn and Olivia De Havilland in 1935, and the novel is better than the film. Brazen pirates prowl the Caribbean in the late sixteen hundreds, battling each other and the ships of European governments to win gold and honor and, of course, the most attractive or available women. Into this maelstrom sails a man described in the book’s opening sentence:

Peter Blood, bachelor of medicine and several other things besides, smoked a pipe and tended the geraniums boxed on the sill of his window above Water Lane in the town of Bridgewater.

Soon this erudite gentleman is swept out to sea on a pirate ship and the bold, funny, bawdy adventures begin. You’ll love every swashbuckling moment of it, as we did.

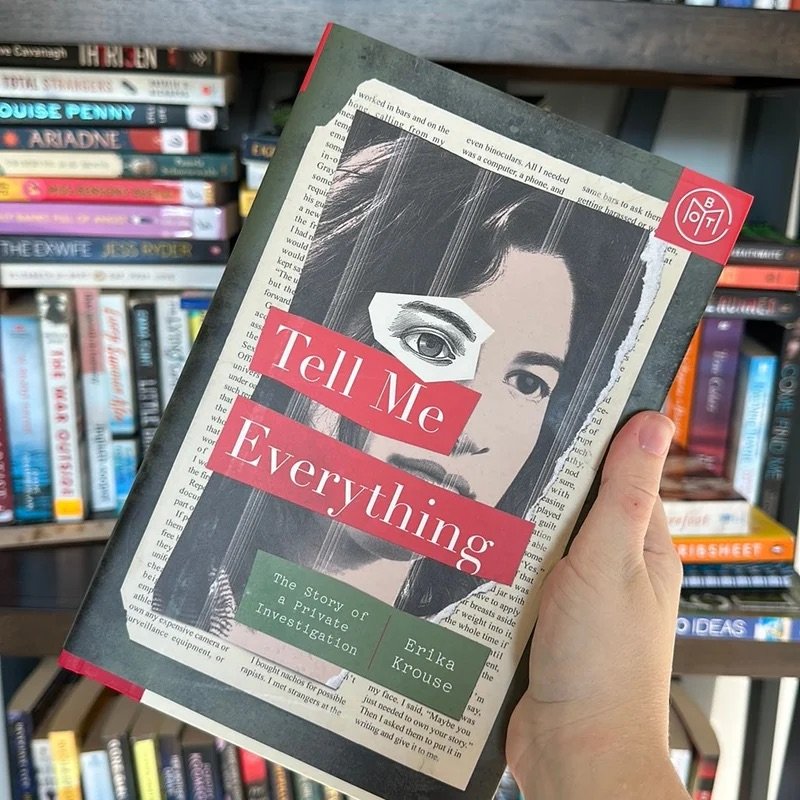

Perhaps the sleeper in this list, since some of the others are more well-known, is Tell Me Everything: The Story of a Private Investigation, a true story written by Erika Krouse. Krouse is a private investigator hired by a lawyer to look into charges of assault on a woman by members of a university football team in Colorado. What follows is the unravelling of a culture of sexual harassment in which everyone from players and coaches to administrators and monied backers of the team conspire not only to discredit the charges but to allow the violent culture to continue. Krause persists in her efforts despite the gathering opposition which threatens both her case against the perpetrators and her own safety. Over five years, she uncovers not just one university’s scandal but a national culture of abuse that permeates college athletics. She is a brave woman and a terrific writer.

I read my first Haruki Murakami novel twenty years ago and have dabbled ever since. My grandson Joe was assigned Murakami’s 2001 novel Sputnik Sweetheart this fall as a high school junior, so I read it with him. The sputnik in the title is a confusion in language; one character cannot remember the word beatnik to describe an unconventional partner but recalls instead the name of the Russian satellite. This kind of misunderstanding, and the layering of contradictory realities, is part of what makes Murakami’s writing so captivating. Two thirds of the way through the story one of the central characters simply disappears, and no amount of searching on a small Greek island turns up a single clue about what happened to her. But of course – this is Murakami – she shows up to her grieving lover near the end, in a late-night conversation that may be a dream, but maybe not. I’d forgotten what a powerful, sometimes lyrical writer Murakami is, and how his interweaving of blunt realism and intoxicating surrealism makes reading him an experience of constant surprise. The odd characters in this story somehow relate in ways that defy convention but are still persuasive as deep and self-revealing friends and lovers. Perhaps like me, you’ll be back again to dip into his unconventional characters in their unconventional but compelling worlds.

Finally, a farewell bow to Cormac McCarthy, who died last winter at ninety, just a few months after publishing not one but two companion novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris. I began reading his novels in the 1980s but lost track of him in recent years. It was my curiosity about a ninety-year-old simultaneously publishing not one but two final books that sent me to his last two efforts. Like Octavia Butler, McCarthy has never shied away from our culture’s underbelly. The Passenger exposes the hostile, cruel, dangerous layers of our culture that we want to look away from: betrayal and death, mental illness and sexual deviance, vengeance and isolation. As in many of McCarthy’s stories, there is someone or something out there, not clearly identified but waiting – and always dangerous. It’s amazing how the ninety-year-old McCarthy’s story-telling and luminous writing are still there on page after page of The Passenger; it’s alive with memorable characters caught in a riveting plot that remains clouded in an unsolved mystery. It’s a fitting coda for his career. McCarthy’s legacy of compelling stories and brilliant prose carve out a place for him on the Rushmore of writers I’ve depended upon to force me into uncomfortable but revelatory moments. Farewell, Cormac, and thanks for the long, brilliant literary ride.

Thanks for reading I’ve Been Thinking! Subscribe for free to receive new essays directly to your email inbox as they’re published.